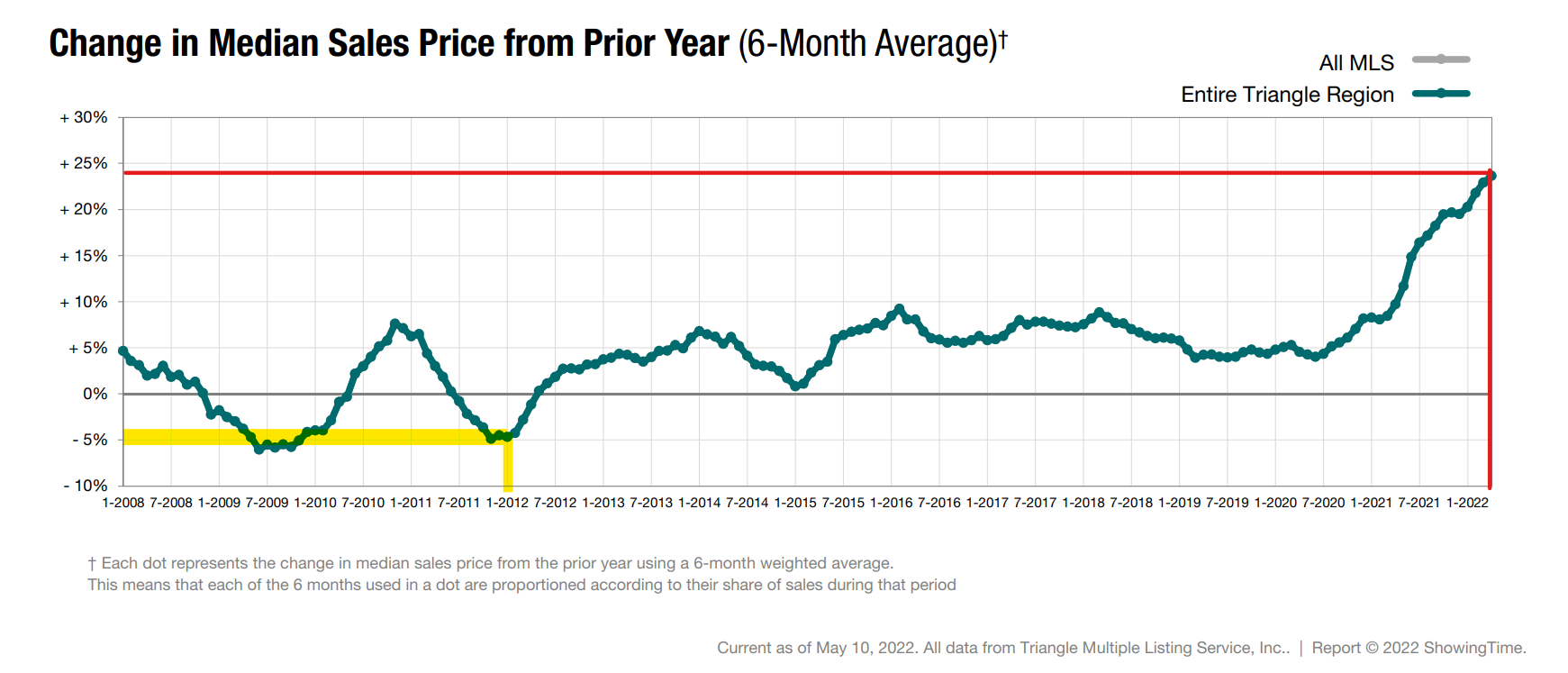

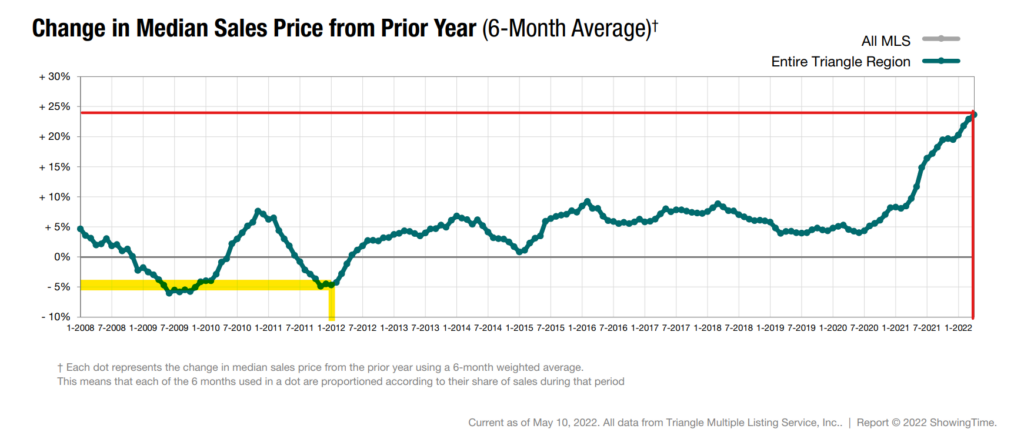

What a difference a decade makes. In 2012, the country was a couple of years into its recovery from the “Great Recession” and real estate prices across North Carolina were still lagging behind their 2007 peak. In 2022, the country is a couple of years into its recovery from the “COVID Recession” and real estate prices are BOOMING. Home prices in North Carolina increased 45% from March 2020 to March 2022 and continue to pick up steam.

The chart above shows the change in the median home sales price in the Raleigh/Durham/Chapel Hill region for the past 14 years. I added the red lines to show where we are today (nearly 25% increase over prior year’s sales prices) and the yellow lines show where we were in 2012 (5% decrease). Back in 2012, the Triangle experienced two years of larger and larger price decreases. Today, the Triangle is in the midst of two years of larger and larger price increases with no sign of a slowdown.

The skyrocketing North Carolina real estate market of course impacts local property tax bases. But because counties do not reappraise real property every year, it takes time for that impact to be visible.

Under G.S. 105-286, counties may wait as long as 8 years in between real property tax reappraisals. As a result, it might be years before a county’s tax base reflects increasing market prices. The most common county reappraisal cycles are 8 years and 4 years, with many counties moving from the former to the latter recently. I believe that Durham County’s recent 3-year cycle was the state’s shortest. In between those county-wide reappraisals, individual property tax appraisals should not change due to economic or market forces.

The lag between market prices and tax appraisals is often highlighted by the N.C. Department of Revenue’s annual sales assessment ratio (“SAR”) report. The SAR measures the ratio between a property’s tax appraisal and its actual sale price. If the tax appraisal and sales price are identical, the ratio is expressed as 100. If the ratio is over 100, that means the tax appraisal was greater than the sales price. If the ratio is below 100, the reverse is true; the tax appraisal was less than the sales price.

Each year, the Department of Revenue analyzes a sample of actual real property sales in each of the state’s 100 counties and calculates an average SAR for each county. If a county’s average SAR is over 100, then on average that county’s tax appraisals are above market value. If a county’s average SAR is below 100, then on average that county’s tax appraisals are below market value.

A county’s SAR is usually close to 100 right after a reappraisal and then, as real property prices rise over time but appraisals stay constant, that SAR slowly drops until the county’s next reappraisal. In “normal” economic times, just a handful of counties have SARs above 100 in a given year. But when market prices are dropping as they were in 2012, county SARs actually climb over time and more counties will be above 100. Here’s what I blogged about the 2012 SAR report a decade ago:

Last year, nearly half of the counties hit or exceeded 100, which was astounding. The trend accelerates this year. In the soon-to-be-released 2012 sales assessment ratio study, more than two-thirds of our counties broke the 100 threshold. Equally surprising is the fact that the average sales assessment ratio statewide is now over 100 (it’s 104, to be exact). Clay County leads the pack with a ratio of 142 . . .

Ten years later, the the annual SAR report looks almost completely inverted from the 2012 version. Thanks to the state’s red-hot real estate market, in 2022 only 3 counties have average SARs above 100. The average SAR is 84 and the highest is only 103.

What do this year’s low SARs mean for property taxes going forward?

First, most counties can expect a substantial increase in their property tax bases when they next reappraise and finally capture the increase in market prices that the state has been experiencing in recent years. This may allow those counties to lower their tax rates substantially if they don’t increase their budgets at the same rate as their tax bases have expanded.

Consider this example. There were seven counties with average SARs below 70 in the 2022 SAR report. If one of those counties conducts a reappraisal that sets its appraisals at market value, then that county’s tax base will increase by more than 40%. Here’s the math: a property that is appraised at $70,000 with a true market value of $100,000 should receive a new appraisal of $100,000; that new appraisal of $100,000 is 42% larger than the old appraisal of $70,000.

Second, counties are at risk of losing some of the public service company property value allocated to them annually by the Department of Revenue if their average SARs fall below 90. (See G.S. 105-284(b).) This year, 74 counties have average SARs below that threshold.

Finally, counties with populations of 75,000 or more that have average SARs under 85 or over 115 will be required to reappraise their real property within three years if they don’t already have a reappraisal scheduled within that time period. (See G.S. 105-286(a)(2).)

Although about two-thirds of our state’s counties have average SARs below 85 this year, I think only one (Wayne County) will trigger the mandatory reappraisal provision in G.S. 105-286 because the others either (i) don’t meet the 75,000 population threshold or (ii) already have reappraisals scheduled within the next three years. But of course that could change next year if market prices continue to rise and average SARs continue to plummet.