A Refresher on North Carolina’s Needle Exchange Law and Other Harm Reduction Immunities

Published: 01/30/23

Author Name: Guest Blogger

[By SOG faculty member Phil Dixon]

In response to the opioid crisis, North Carolina passed several protections designed to alleviate some of the legal liability surrounding drug use in the interest of harm reduction and public health. One of those protections authorized needle exchange programs (alternatively known as safe syringes programs). G.S. 90-113.27. A recent study examined how the needle exchange program is working in seven North Carolina counties and found that the law was not consistently applied. Brandon Morrison et al., “They Don’t Go by the Law Around Here”: Law Enforcement Interactions After the Legalization of Syringe Services Programs in North Carolina, vol. 19, Harm Reduction Journal, 106 (Sept. 27, 2022). Considering the study’s findings, I thought a refresher on the immunity provisions for syringe exchanges and similar protections would be timely. Read on for the details.

The Needle Exchange Law. The legislature first authorized needle exchange programs in 2016. Under the law, an organization wishing to engage in this kind of program must dispense unused syringes and other injection supplies, dispose of used needles, provide educational material on drug treatment and safe drug use practices, and provide access to the overdose treatment drug Naloxone. They also must provide mental health and drug treatment consultations upon request. Before beginning such a program, the organization must register with the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (“DHHS”) and thereafter report annually to DHHS concerning the extent of their services.

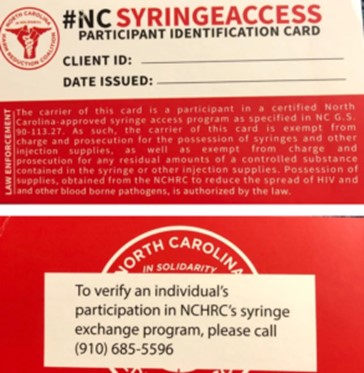

Participants in the program are provided written verification (usually in the form of a card) documenting that the injection supplies came from an authorized needle exchange program, which typically provides a phone number for law enforcement to verify the person’s participation in the program. Those cards can vary a bit in appearance but tend to look something like this:

Assuming all the requirements of the law are met, any employees or volunteers working within the program are immune from arrest or prosecution, as are any participants in the program (i.e., those receiving services from the program). The immunity extends to residual amounts of drugs found in used syringes or other injection supplies, in addition to the syringes and other injection supplies.

The law also provides limited immunity for law enforcement. Under subsection G.S. 90-113.27(c), an officer is protected from civil liability for arresting or charging a person who falls within the protections of the law if the officer was acting in good faith.

How Syringe Exchange Works in Practice. Sounds straightforward enough. According to the findings of the study referenced above, however, the picture on the ground is not so neat. In short, the authors found widespread differences in how law enforcement responds to claims of immunity under the needle exchange law. “Coercive” (in the words of the study) encounters with law enforcement—defined as the improper seizure of injection supplies, seizure of the card documenting a person’s participation in the program, or arrest of a participant for possession of supplies provided by the syringe exchange program—were reported in every county examined. In addition to those experiences, there were reports of attempts by law enforcement to recruit participants into informant work following an encounter where the person admitted to participation in the program. A particularly high number of Black women reported experiences of law enforcement doubting their ownership of the documentation as well. Responses by law enforcement to a claim of immunity thus varied both within a county and from county to county among the seven counties examined. In Haywood County, 47% of survey respondents reported a coercive law enforcement experience. New Hanover County had the next highest numbers, with nearly 35% of respondents reporting a coercive law enforcement experience. On the other end of the spectrum, Johnston and Durham Counties had the lowest numbers of coercive experiences, with around 12% and 16% respectively.

Takeaways. The study concludes by noting that more education and training on the law would likely be useful for law enforcement. Indeed, recall that the law grants immunity to officers for arresting a program participant if the arrest is made in good faith. We do not have any guidance so far as to what constitutes good faith in this area, but it seems likely that complete ignorance of the law would not count, nor would the failure to at least attempt to verify a person’s participation in the program when faced with a colorable claim of immunity. Even seizure of the injection supplies without charging the person—one of the types of problems documented by the study—could presumably result in civil liability if the officer was found to have been acting in bad faith.

Magistrates can help with enforcement of this law as well. Where an officer seeks to charge a person with residual drug amounts found in a syringe or for injection supplies and there is evidence that the person was participating in such a program, the magistrate can rightfully decline to find probable cause, as the person is immune from charge, arrest, or prosecution. Defenders too can help enforce the law by educating clients and court system actors and by raising immunity as a bar to prosecution when applicable. Where there is a legitimate factual dispute about whether a person was actually participating in the program, the bar to arrest or prosecution likely does not apply, and the issue of immunity probably becomes a credibility determination for the finder of fact.

Other Immunities for Harm Reduction. There are a few other immunity provisions relevant in this area that may be useful to keep in mind. Recall that the drug paraphernalia law was amended to exclude drug testing kits from its reach. Thus, it is no longer illegal for a person or organization to possess, sell, or distribute testing kits used for determining the identity and purity of an illegal drug. See G.S. 90-113.22(d). The paraphernalia law was also amended to protect anyone who discloses to law enforcement the existence of a syringe or other sharp object on their person, premise, or vehicle prior to a search. Under G.S. 90-113.22(c), if a person about to be searched by law enforcement informs the officer ahead of time of the sharp object, the person may not be charged or prosecuted for paraphernalia or possession of any residual amounts present within the syringe.

Under our so-called Good Samaritan law, G.S. 90-96.2, there is limited immunity for people reporting an overdose and for the overdosing person under certain circumstances. This law only covers misdemeanor possession offenses, paraphernalia offenses, and felony offenses involving less than one gram of cocaine or heroin. Fentanyl and its derivatives or mixtures of drugs including those substances are notably not covered.

Finally, people distributing or administering the overdose prevention drug Naloxone (also known by it trade name Narcan) have limited immunity under G.S. 90-96.2. Something I learned while preparing this post was that any person in a position to help another person who is at risk of an opiate overdose is lawfully entitled to obtain Naloxone from an authorized source. I have heard of some defenders keeping a supply of the drug on their person or in their offices in order to quickly treat a client or member of the public who experiences an overdose. This fits within the protection of the law, and other individuals or entities regularly interacting with people who use drugs should consider doing the same. If you or someone you know is interested in obtaining Naloxone and believes they qualify as a person authorized to receive it, DHHS has a detailed and well-written toolkit on all things Naloxone and the process of obtaining it, here.

Readers, what are your experiences with the needle exchange laws and other drug immunity provisions in your area? If you are inclined to share, or if you have any questions or concerns, I can be reached as always at dixon@sog.unc.edu.

Special thanks for Anna Stein and Jason Tyler Yates over at NCDHHS for their inspiration and input for this post.

1

Coates’ Canons NC Local Government Law

A Refresher on North Carolina’s Needle Exchange Law and Other Harm Reduction Immunities

Published: 01/30/23

Author Name: Guest Blogger

[By SOG faculty member Phil Dixon]

In response to the opioid crisis, North Carolina passed several protections designed to alleviate some of the legal liability surrounding drug use in the interest of harm reduction and public health. One of those protections authorized needle exchange programs (alternatively known as safe syringes programs). G.S. 90-113.27. A recent study examined how the needle exchange program is working in seven North Carolina counties and found that the law was not consistently applied. Brandon Morrison et al., “They Don’t Go by the Law Around Here”: Law Enforcement Interactions After the Legalization of Syringe Services Programs in North Carolina, vol. 19, Harm Reduction Journal, 106 (Sept. 27, 2022). Considering the study’s findings, I thought a refresher on the immunity provisions for syringe exchanges and similar protections would be timely. Read on for the details.

The Needle Exchange Law. The legislature first authorized needle exchange programs in 2016. Under the law, an organization wishing to engage in this kind of program must dispense unused syringes and other injection supplies, dispose of used needles, provide educational material on drug treatment and safe drug use practices, and provide access to the overdose treatment drug Naloxone. They also must provide mental health and drug treatment consultations upon request. Before beginning such a program, the organization must register with the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (“DHHS”) and thereafter report annually to DHHS concerning the extent of their services.

Participants in the program are provided written verification (usually in the form of a card) documenting that the injection supplies came from an authorized needle exchange program, which typically provides a phone number for law enforcement to verify the person’s participation in the program. Those cards can vary a bit in appearance but tend to look something like this:

Assuming all the requirements of the law are met, any employees or volunteers working within the program are immune from arrest or prosecution, as are any participants in the program (i.e., those receiving services from the program). The immunity extends to residual amounts of drugs found in used syringes or other injection supplies, in addition to the syringes and other injection supplies.

The law also provides limited immunity for law enforcement. Under subsection G.S. 90-113.27(c), an officer is protected from civil liability for arresting or charging a person who falls within the protections of the law if the officer was acting in good faith.

How Syringe Exchange Works in Practice. Sounds straightforward enough. According to the findings of the study referenced above, however, the picture on the ground is not so neat. In short, the authors found widespread differences in how law enforcement responds to claims of immunity under the needle exchange law. “Coercive” (in the words of the study) encounters with law enforcement—defined as the improper seizure of injection supplies, seizure of the card documenting a person’s participation in the program, or arrest of a participant for possession of supplies provided by the syringe exchange program—were reported in every county examined. In addition to those experiences, there were reports of attempts by law enforcement to recruit participants into informant work following an encounter where the person admitted to participation in the program. A particularly high number of Black women reported experiences of law enforcement doubting their ownership of the documentation as well. Responses by law enforcement to a claim of immunity thus varied both within a county and from county to county among the seven counties examined. In Haywood County, 47% of survey respondents reported a coercive law enforcement experience. New Hanover County had the next highest numbers, with nearly 35% of respondents reporting a coercive law enforcement experience. On the other end of the spectrum, Johnston and Durham Counties had the lowest numbers of coercive experiences, with around 12% and 16% respectively.

Takeaways. The study concludes by noting that more education and training on the law would likely be useful for law enforcement. Indeed, recall that the law grants immunity to officers for arresting a program participant if the arrest is made in good faith. We do not have any guidance so far as to what constitutes good faith in this area, but it seems likely that complete ignorance of the law would not count, nor would the failure to at least attempt to verify a person’s participation in the program when faced with a colorable claim of immunity. Even seizure of the injection supplies without charging the person—one of the types of problems documented by the study—could presumably result in civil liability if the officer was found to have been acting in bad faith.

Magistrates can help with enforcement of this law as well. Where an officer seeks to charge a person with residual drug amounts found in a syringe or for injection supplies and there is evidence that the person was participating in such a program, the magistrate can rightfully decline to find probable cause, as the person is immune from charge, arrest, or prosecution. Defenders too can help enforce the law by educating clients and court system actors and by raising immunity as a bar to prosecution when applicable. Where there is a legitimate factual dispute about whether a person was actually participating in the program, the bar to arrest or prosecution likely does not apply, and the issue of immunity probably becomes a credibility determination for the finder of fact.

Other Immunities for Harm Reduction. There are a few other immunity provisions relevant in this area that may be useful to keep in mind. Recall that the drug paraphernalia law was amended to exclude drug testing kits from its reach. Thus, it is no longer illegal for a person or organization to possess, sell, or distribute testing kits used for determining the identity and purity of an illegal drug. See G.S. 90-113.22(d). The paraphernalia law was also amended to protect anyone who discloses to law enforcement the existence of a syringe or other sharp object on their person, premise, or vehicle prior to a search. Under G.S. 90-113.22(c), if a person about to be searched by law enforcement informs the officer ahead of time of the sharp object, the person may not be charged or prosecuted for paraphernalia or possession of any residual amounts present within the syringe.

Under our so-called Good Samaritan law, G.S. 90-96.2, there is limited immunity for people reporting an overdose and for the overdosing person under certain circumstances. This law only covers misdemeanor possession offenses, paraphernalia offenses, and felony offenses involving less than one gram of cocaine or heroin. Fentanyl and its derivatives or mixtures of drugs including those substances are notably not covered.

Finally, people distributing or administering the overdose prevention drug Naloxone (also known by it trade name Narcan) have limited immunity under G.S. 90-96.2. Something I learned while preparing this post was that any person in a position to help another person who is at risk of an opiate overdose is lawfully entitled to obtain Naloxone from an authorized source. I have heard of some defenders keeping a supply of the drug on their person or in their offices in order to quickly treat a client or member of the public who experiences an overdose. This fits within the protection of the law, and other individuals or entities regularly interacting with people who use drugs should consider doing the same. If you or someone you know is interested in obtaining Naloxone and believes they qualify as a person authorized to receive it, DHHS has a detailed and well-written toolkit on all things Naloxone and the process of obtaining it, here.

Readers, what are your experiences with the needle exchange laws and other drug immunity provisions in your area? If you are inclined to share, or if you have any questions or concerns, I can be reached as always at dixon@sog.unc.edu.

Special thanks for Anna Stein and Jason Tyler Yates over at NCDHHS for their inspiration and input for this post.

All rights reserved. This blog post is published and posted online by the School of Government to address issues of interest to government officials. This blog post is for educational and informational use and may be used for those purposes without permission by providing acknowledgment of its source. Use of this blog post for commercial purposes is prohibited. To browse a complete catalog of School of Government publications, please visit the School’s website at www.sog.unc.edu or contact the Bookstore, School of Government, CB# 3330 Knapp-Sanders Building, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3330; e-mail sales@sog.unc.edu; telephone 919.966.4119; or fax 919.962.2707.