Every local government and public authority begins the fiscal year with an annual budget ordinance. The ordinance shows the unit’s best estimate of the revenue it expects to receive and the expenditures it expects to make during the year. These estimates guide operations, but they will never match reality perfectly. Needs change, information improves, and conditions shift during the year. When that happens, the unit may need to revise the budget ordinance.

This post explains when a budget amendment is required, who may adopt it, and how amendments differ from internal budget adjustments. It also offers guidance for building a clear internal process for amendments and adjustments so the budget functions smoothly throughout the year.

The Annual Budget Ordinance

State law sets the requirements for a valid annual budget ordinance. G.S. 159-13 leaves the specific budget format up to each unit, but there are certain required elements.

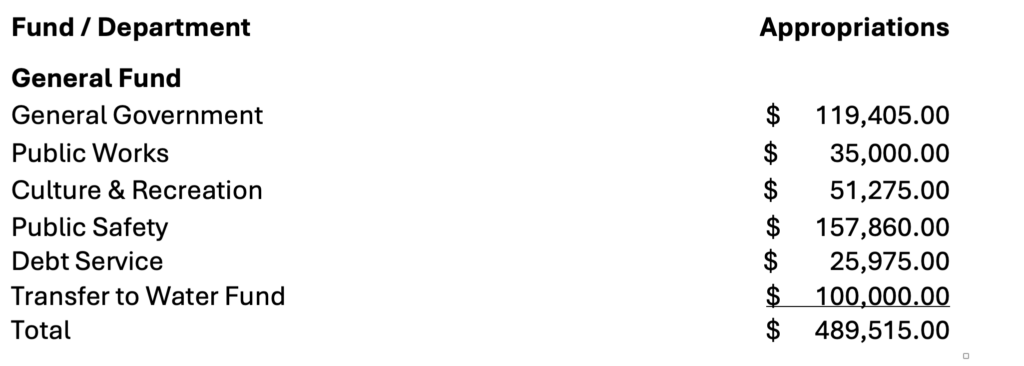

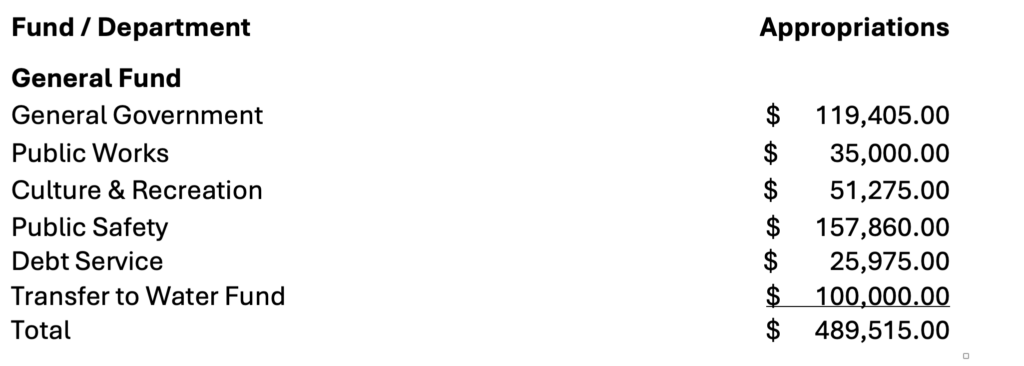

1. The budget ordinance must be broken down by funds. All units must have a general fund. Other funds may be required, in accordance with G.S. 159-26, based on the unit’s activities.

2. Within each fund, the budget ordinance must:

- List estimated revenues by major source

- Make appropriations by department, function, or project (Appropriations may not be made at the fund level or at the line item level. There also may not be appropriations to specific nonprofits or other private entities.)

- Appropriate fund balance, if needed to balance the budget

- Set amounts such that estimated revenues + appropriated fund balance = appropriations, and

- Authorize transfers to other funds, if any.

3. The budget ordinance must include all property tax levy(ies), including the general tax levy(ies) and any special district tax levies (for tax-levying entities only).

4. The budget ordinance must abide by other requirements and limitations set out in G.S. 159-8 and G.S. 159-13.

5. Governing board member compensation must be set in the budget ordinance.

6. [For counties only] Budget ordinance must specify appropriations to local school administrative unit(s)’ Local Current Expense Fund and Capital Outlay Fund, in accordance with G.S. 115C-426.

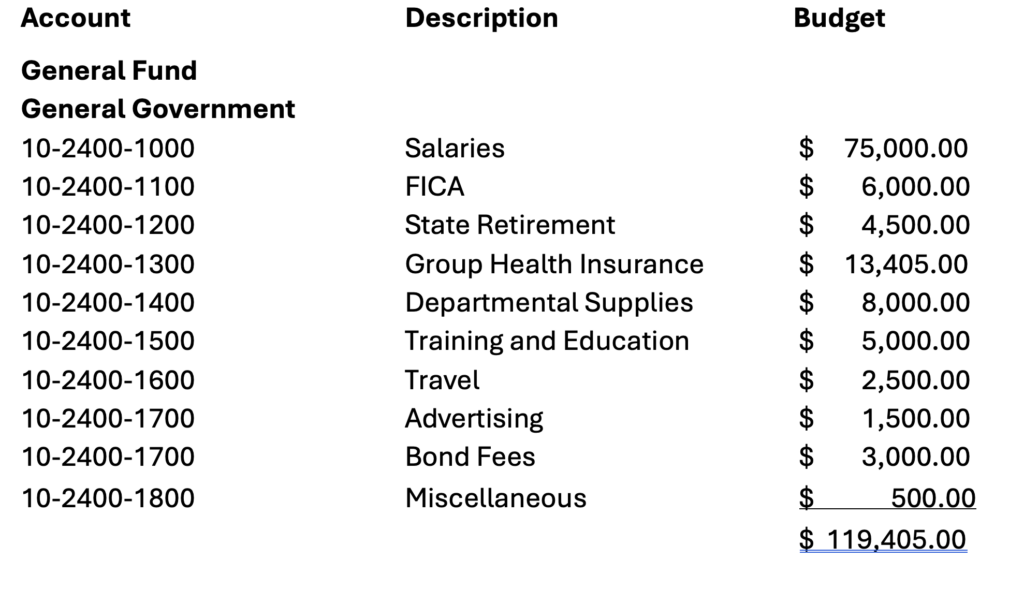

Working Budget

After the board adopts the ordinance, budget and finance staff convert the legal appropriations into a working spending plan. They break departments, functions, and/or projects into account codes based on the unit’s chart of accounts. These line items guide daily activity but do not carry legal weight. (The working budget might be included as part of the adopted budget, but it is not the legal budget ordinance.)

To illustrate the difference, assume the following appropriations by department in the annual budget ordinance:

Here is a snapshot of how those appropriations might be broken up in a working budget, focused only on the General Government department:

When a Budget Amendment is Required

A unit amends its annual budget ordinance only when it needs to make a legal change to the ordinance itself. Many day-to-day financial adjustments during the year do not require a formal amendment.

A budget amendment is required only when the unit wants, or needs, to do one of the following:

- move appropriations between departments, functions, or projects within a fund (recall that appropriations must be made by department, function, or project)

- change revenue estimates to add new revenues or to increase or decrease existing revenue estimates

- increase or decrease appropriated fund balance

- move appropriations or revenues between funds

The Obligation Rule

Sometimes an amendment is legally required because of the timing of a new obligation. A unit must amend the budget ordinance when it wants to enter into a new obligation that, when added to all existing encumbrances in a department, function, or project, would exceed the current appropriation for that department, function, or project. An obligation is the legal commitment to pay someone, such as issuing a purchase order or signing a service or construction contract. It triggers the preaudit requirement in G.S. 159-28. A unit may not enter into an obligation that exceeds the legal appropriation, so if the appropriation is too low, the amendment must come first. Otherwise the unit risks a budget violation. However, an amendment is not legally required when an obligation would exceed only a line-item within a department, function, or project.

Revenue Changes

Actual revenues will rarely match the original estimates. The governing board is not required to revise those estimates when revenues run higher or lower than expected. A revenue amendment is legally required only when the board intends to spend new revenues—either revenues from a new source or an increase in an existing source—that were not included in the original ordinance.

Even when not required, it is often wise for the board to amend the budget to reflect actual revenue collections, especially when revenues fall short. If the board chooses to bring estimates down to match reality, the board must either reduce appropriations or appropriate additional fund balance to keep the budget balanced. If the board chooses not to amend the ordinance, it may instead direct staff to limit obligations and spending to stay within available resources. Regardless of any amendments, the finance officer must separately monitor cash and ensure the unit has enough money in the bank to cover all disbursements.

Substantive Budget Amendment Limitations

As detailed in the previous post, state law also places several substantive limits on what budget amendments may do, including prohibitions on changing the tax levy except in very limited circumstances, prohibitions on altering board member compensation during the fiscal year, and restrictions on reducing appropriations to local school administrative units unless narrow exceptions apply.

Who May Make Budget Ordinance Amendments

The budget ordinance is adopted by the unit’s governing board. G.S. 159-15 also requires that the governing board make any amendments to that ordinance. The statute provides that “the budget ordinance may be amended by the governing board at any time after the ordinance’s adoption… so long as the ordinance, as amended, continues to satisfy the requirements of G.S. 159-8 and 159-13.” When a statute assigns a responsibility to the governing board, the board may not delegate that responsibility unless the statute itself creates an express exception. As a result, the general rule is that only the governing board may amend the budget ordinance.

G.S. 159-15 creates one narrow exception to that general rule. It allows the governing board, “by appropriate resolution or ordinance,” to authorize the budget officer, and only the budget officer, “to transfer moneys from one appropriation to another within the same fund,” subject to any limits or procedures the board sets. The board may grant broad authority for these within-fund transfers or may restrict the delegation by setting dollar caps, limiting transfers to specific departments or functions, or requiring additional internal approvals. This delegated authority extends only to transfers between appropriations within the same fund. The board may not authorize the budget officer (or anyone else) to make any other type of budget amendment. All other amendments must be adopted by the governing board itself. Any amendments made under this delegated authority must be reported to the governing board at its next regular meeting and entered in the minutes.

Because only the budget officer may exercise this delegated authority, it is important to understand who may serve in that role. G.S. 159-9 requires every local government and public authority to appoint a budget officer, but the statute sets different rules depending on the unit’s form of government. In counties and in municipalities with the manager form of government, the manager must serve as the budget officer. State law prohibits the mayor or any council member in a manager-form municipality from serving as manager, even on an acting or interim basis. As a result, elected officials in a manager-form city are also ineligible to serve as the budget officer. Municipalities that do not have the manager form of government have more discretion. Their governing boards may assign the duties of budget officer to any municipal officer or employee. This may include the mayor, but only if the mayor agrees to undertake the administrative responsibilities of the role. Public authorities and special districts have similar flexibility. They may assign the duties of budget officer to the chair, another member of the governing board, or any officer or employee of the authority or district.

Tracking Budget Amendments

A unit needs a clear method to track amendments throughout the fiscal year. Several approaches work well:

- a standing amendment log for the full year

- attachments to board minutes with a year-end summary

- monthly or quarterly amendment reports

- software tags or notes that link transactions to specific amendments

Any method is acceptable as long as each amendment is documented, the approval authority is clear, and the record is easy to review. Units also may choose, as an internal policy matter, to bring certain amendments to the governing board for approval even when state law does not require it. The statute dictates when amendments are legally required, but units may adopt a higher bar for board involvement if they find it helpful.

Budget Adjustments

Once the governing board (or the budget officer under delegated authority) adopts a budget amendment, the legal budget ordinance is updated. But daily financial management still requires flexibility. Staff often need to reallocate funds within a department, function, or project as circumstances change. Units handle these routine changes through budget adjustments.

What Budget Adjustments Are

Budget adjustments move money between account codes within a single department, function, or project. They help staff manage the working budget but do not change the budget ordinance and have no legal effect under state law. Units use different labels for the same concept, including adjustments, transfers, internal amendments, budget revisions, or journal entries. Regardless of the term, these are internal administrative tools, not legal budget amendments.

Why an Adjustment Policy Is Necessary

Because state law does not address internal adjustments, each unit must adopt its own rules. Without a written policy, departments may follow inconsistent practices, staff may be unsure who has authority to move funds, and internal control gaps may develop. A clear adjustment policy provides structure, promotes consistent decision-making, and helps avoid confusion or conflict. It gives department heads and finance staff a shared understanding of when and how these internal budget changes occur. The governing board should adopt the policy or direct the budget officer to develop one.

What an Adjustment Policy Should Cover

An effective adjustment policy should specify

- when adjustments must or may occur,

- who may request them,

- who must approve them,

- who records them in the accounting system,

- what documentation is required, and

- how (or whether) the governing board will be notified.

Some units prefer stronger oversight and require the governing board to approve every adjustment. This is permitted as a matter of local policy, though it is not required by statute. Other units take a more targeted approach by imposing specific limits. For example, they may prohibit adjustments to salary or benefits lines without board approval, restrict shifts between operating and capital categories, or require board notification when an adjustment exceeds a set dollar amount. Some units also require staff to enter an adjustment before any obligation exceeds a line-item account code, even when the overall department or function has sufficient appropriation.

A unit’s financial software may also affect when adjustments are needed. Certain systems will not allow a purchase order, obligation, or payment to proceed unless the individual line-item account has enough budgeted funds. In those cases, staff may need to enter an adjustment solely to satisfy software controls, even if the legal appropriation is adequate. The adjustment policy should address how staff should navigate these system requirements.

All of these choices are permissible internal controls. They reflect local preferences and help define how staff manage the working budget throughout the year.

Who Must Follow the Policy

Once the unit decides how internal adjustments will be handled, the next question is who is required to follow the policy. The budget officer should implement or develop the policy based on the governing board’s direction, and the policy should be in writing and shared with department heads, finance staff, and anyone responsible for managing budgets. In practice, compliance is enforced through supervisory authority. Employees who do not follow the policy may be subject to standard personnel tools, including corrective action or discipline.

In counties, applying the policy to independently elected or appointed officials is more complex. These officials, such as the sheriff, register of deeds, soil and water conservation supervisor, and the local board of elections / director of elections, do not fall within the governing board’s or budget officer / county manager’s direct supervisory chain. The policy still communicates the county’s expectations, and many such officials follow it as a matter of good practice, but enforcement relies on cooperation rather than managerial control.

It is also important to clarify the finance officer’s role. A finance officer may not decline to preaudit an obligation from one of these officials simply because it does not follow the county’s line-item adjustment policy. The preaudit requirement focuses on whether the obligation would exceed the legal appropriation at the department, function, or project level. If sufficient appropriation exists at that legal level, the finance officer should complete the preaudit, even if the transaction would exceed a line-item account or fall outside the county’s preferred internal procedures.

These officials must still comply with all statutory requirements for legal budget ordinance amendments and may not exceed the legal appropriation for their department, function, or project. As long as they remain within that legal appropriation and within their contracting authority, they may incur obligations beyond individual line-item account codes.

Putting It All Together

Budget amendments and budget adjustments play different roles in managing a local government’s finances. Budget amendments change the legal budget ordinance and must follow the statutory rules for when they are required and who may adopt them. Budget adjustments are internal tools that help staff manage the working budget within the limits set by the ordinance. Since state law does not regulate adjustments, each unit must create clear internal policies that reflect the governing board’s expectations and support sound financial management.